While all Muslims believe that they are on the pathway to God and

hope to become close to God in Paradise—after death and after the "Final

Judgment"—Sufis also believe that it is possible to draw closer to God

and to more fully embrace the

Divine Presence in this life.

[24] The chief aim of all Sufis is to seek the pleasing of God by working to restore within themselves the primordial state of

fitra,

[25] described in the Qur'an. In this state nothing one does defies God, and all is undertaken with the single motivation of

love of God. A secondary consequence of this is that the seeker may be led to abandon all notions of

dualism or multiplicity, including a conception of an individual

self, and to realize the

Divine Unity.

[citation needed]

Thus, Sufism has been characterized

[by whom?]

as the science of the states of the lower self (the ego), and the way

of purifying this lower self of its reprehensible traits, while adorning

it instead with what is praiseworthy, whether or not this process of

cleansing and purifying the heart is in time rewarded by esoteric

knowledge of God. This can be conceived in terms of two basic types of

law (

fiqh), an outer law concerned with actions, and an inner law concerned with the human heart.

[citation needed]

The outer law consists of rules pertaining to worship, transactions,

marriage, judicial rulings, and criminal law—what is often referred to, a

bit too broadly, as

qanun.

The inner law of Sufism consists of rules about repentance from sin,

the purging of contemptible qualities and evil traits of character, and

adornment with virtues and good character.

[26]

Sufism, which is a general term for Muslim mysticism, was originally a

response to the increasing worldly power of Islamic leaders as the

religion spread during the 8th Century and their corresponding shift in

focus towards materialistic and political concerns.

[citation needed] In particular,

Harun al-Rashid, the fifth

Abbasid Caliph,

attracted negative attention for his lavish lifestyle, including gold

and silver tableware, an extensive harem and numerous slaves and

retainers, that stood in contrast to the relative simplicity of

Muhammad's life.

[citation needed]

The typical early Sufi lived in a cell of a mosque and taught a small

band of disciples. The extent to which Sufism was influenced by

Buddhist and Hindu mysticism, and by the example of Christian hermits

and monks, is disputed, but self-discipline and concentration on God

quickly led to the belief that by quelling the self and through loving

ardour for God it is possible to maintain a union with the divine in

which the human self melts away.

[27]

Teaching

To enter the way of Sufism, the seeker begins by finding a teacher,

as the connection to the teacher is considered necessary for the growth

of the pupil. The teacher, to be considered genuine, must have received

the authorization to teach (

ijazah) from another Master of the Way, in an unbroken succession (

silsilah) leading back to Muhammad.

[dubious – discuss][citation needed]

It is the transmission of the divine light from the teacher's heart to

the heart of the student, rather than of worldly knowledge transmitted

from mouth to ear, that allows the adept to progress. In addition, the

genuine teacher will be utterly strict in his adherence to the Divine

Law.

[28]

According to

Moojan Momen "one of the most important doctrines of Sufism is the concept of the "Perfect Man" (

al-Insan al-Kamil). This doctrine states that there will always exist upon the earth a "

Qutb" (Pole or Axis, of the Universe)—a man who is the perfect channel of grace from God to man and in a state of

wilaya (sanctity, being under the protection of God). The concept of the Sufi Qutb is similar to that of the

Shi'i Imam.

[29]

However, this belief puts Sufism in "direct conflict" with Shi'ism,

since both the Qutb (who for most Sufi orders is the head of the order)

and the Imam fulfill the role of "the purveyor of spiritual guidance and

of God's grace to mankind". The vow of obedience to the Shaykh or Qutb

which is taken by Sufis is considered incompatible with devotion to the

Imam".

[29]

As a further example, the prospective adherent of the

Mevlevi

Order would have been ordered to serve in the kitchens of a hospice for

the poor for 1,001 days prior to being accepted for spiritual

instruction, and a further 1,001 days in solitary retreat as a

precondition of completing that instruction.

[30]

Some teachers, especially when addressing more general audiences, or

mixed groups of Muslims and non-Muslims, make extensive use of

parable,

allegory, and

metaphor.

[31]

Although approaches to teaching vary among different Sufi orders,

Sufism as a whole is primarily concerned with direct personal

experience, and as such has sometimes been compared to other,

non-Islamic forms of

mysticism (e.g., as in the books of

Hossein Nasr).

Scholars and adherents of Sufism are unanimous in agreeing that Sufism cannot be learned through books.

[dubious – discuss]

To reach the highest levels of success in Sufism typically requires

that the disciple live with and serve the teacher for many, many years.

[citation needed] For instance,

Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari, who gave his name to the

Naqshbandi

Order, served his first teacher, Sayyid Muhammad Baba As-Samasi, for 20

years, until as-Samasi died. He subsequently served several other

teachers for lengthy periods of time. The extreme arduousness of his

spiritual preparation is illustrated by his service, as directed by his

teacher, to the weak and needy members of his community in a state of

complete humility and tolerance for many years. When he believed this

mission to be concluded, his teacher next directed him to care for

animals, curing their sicknesses, cleaning their wounds, and assisting

them in finding provision. After many years of this he was next

instructed to spend many years in the care of dogs in a state of

humility, and to ask them for support.

[32]

History of Sufism

Origins

Practitioners of Sufism hold that in its early stages of development

Sufism effectively referred to nothing more than the internalization of

Islam.

[33]

According to one perspective, it is directly from the Qur'an,

constantly recited, meditated, and experienced, that Sufism proceeded,

in its origin and its development.

[34] Others have held that Sufism is the strict emulation of the way of

Muhammad, through which the heart's connection to the Divine is strengthened.

[35]

More prosaically, the

Muslim Conquests

had brought large numbers of Christian monks and hermits, especially in

Syria and Egypt, under the rule of Muslims. They retained a vigorous

spiritual life for centuries after the conquests, and many of the

especially pious Muslims who founded Sufism were influenced by their

techniques and methods.

[36] According to late Medieval mystic

Jami,

Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah was the first person to be called a "Sufi."

[20]

Important contributions in writing are attributed to

Uwais al-Qarni, Harrm bin Hian,

Hasan Basri and Sayid ibn al-Mussib.

Ruwaym, from the second generation of Sufis in Baghdad, was also an influential early figure,

[37][38] as was

Junayd of Baghdad; a number of early practitioners of Sufism were disciples of one of the two.

[39]

Sufism had a long history already before the subsequent institutionalization of Sufi teachings into devotional orders (

tarîqât) in the early Middle Ages.

[40] The

Naqshbandi

order is a notable exception to general rule of orders tracing their

spiritual lineage through Muhammad's grandsons, as it traces the origin

of its teachings from Muhammad to the first Islamic Caliph,

Abu Bakr.

[5]

Formalization of doctrine

Towards the end of the first millennium CE, a number of manuals began

to be written summarizing the doctrines of Sufism and describing some

typical Sufi practices. Two of the most famous of these are now

available in English translation: the

Kashf al-Mahjûb of

Hujwiri, and the

Risâla of

Qushayri.

[41]

Two of Imam

Al Ghazali's

greatest treatises, the "Revival of Religious Sciences" and the

"Alchemy of Happiness", argued that Sufism originated from the Qur'an

and was thus compatible with mainstream Islamic thought, and did not in

any way contradict Islamic Law—being instead necessary to its complete

fulfillment. This became the mainstream position among Islamic scholars

for centuries, challenged only recently on the basis of selective use of

a limited body of texts.

[example needed]

Ongoing efforts by both traditionally trained Muslim scholars and

Western academics are making Imam Al-Ghazali's works available in

English translation for the first time,

[42] allowing English-speaking readers to judge for themselves the compatibility of Islamic Law and Sufi doctrine.

Growth of influence

The rise of Islamic civilization coincides strongly with the spread

of Sufi philosophy in Islam. The spread of Sufism has been considered a

definitive factor in the spread of Islam, and in the creation of

integrally Islamic cultures, especially in Africa

[43] and Asia. The

Senussi tribes of Libya and Sudan are one of the strongest adherents of Sufism. Sufi poets and philosophers such as

Rumi and

Attar of Nishapur greatly enhanced the spread of Islamic culture in Anatolia, Central Asia, and South Asia.

[44][45] Sufism also played a role in creating and propagating the culture of the

Ottoman world,

[46] and in resisting European imperialism in North Africa and South Asia.

[47]

Between the 13th and 16th centuries CE, Sufism produced a flourishing

intellectual culture throughout the Islamic world, a "Golden Age" whose

physical artifacts are still present. In many places, a lodge (known

variously as a

zaouia,

khanqah, or

tekke) would be endowed through a pious foundation in perpetuity (

waqf)

to provide a gathering place for Sufi adepts, as well as lodging for

itinerant seekers of knowledge. The same system of endowments could also

be used to pay for a complex of buildings, such as that surrounding the

Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, including a lodge for Sufi seekers, a

hospice

with kitchens where these seekers could serve the poor and/or complete a

period of initiation, a library, and other structures. No important

domain in the civilization of Islam remained unaffected by Sufism in

this period.

[48]

Contemporary Sufism

Current Sufi orders include

Alians,

Bektashi Order,

Druze,

Mevlevi Order,

Ba 'Alawiyya,

Chishti,

Jerrahi,

Naqshbandi,

Nimatullahi,

Qadiriyyah,

Qalandariyya,

Sarwari Qadiri,

Shadhiliyya,

Suhrawardiyya,

Ashrafia and

Uwaisi (Oveyssi).

[6] The relationship of Sufi orders to modern societies is usually defined by their relationship to governments.

[49]

Turkey and Persia together have been a center for many Sufi lineages and orders. The Bektashi was closely affiliated with the

Ottoman Janissary and is the heart of Turkeys large and mostly liberal

Alevi

population. It has been spread westwards to Cyprus, Greece, Albania,

Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia, Kosovo and more recently to the USA (via

Albania). Most Sufi Orders have influences from pre-Islamic traditions

such as

Pythagoreanism, but the

Turkic Sufi traditions (including Alians, Bektashi and Mevlevi) also have traces of the ancient

Tengrism shamanism.

Sufism is popular in such African countries as

Morocco and

Senegal, where it is seen as a mystical expression of Islam.

[50]

Sufism is traditional in Morocco but has seen a growing revival with

the renewal of Sufism around contemporary spiritual teachers such as

Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Boutshishi. Mbacke suggests that one reason

Sufism has taken hold in Senegal is because it can accommodate local

beliefs and customs, which tend toward the

mystical.

[51]

The life of the Algerian Sufi master Emir

Abd al-Qadir is instructive in this regard.

[52] Notable as well are the lives of

Amadou Bamba and Hajj

Umar Tall in sub-Saharan Africa, and

Sheikh Mansur Ushurma and

Imam Shamil

in the Caucasus region. In the twentieth century some more modernist

Muslims have called Sufism a superstitious religion that holds back

Islamic achievement in the fields of science and technology.

[53]

A number of Westerners have embarked with varying degrees of success

on the path of Sufism. One of the first to return to Europe as an

official representative of a Sufi order, and with the specific purpose

to spread Sufism in Western Europe, was the

Swedish-born wandering Sufi

Abd al-Hadi Aqhili (also known as Ivan Aguéli).

René Guénon,

the French scholar, became a Sufi in the early twentieth century and

was known as Sheikh Abdul Wahid Yahya. His manifold writings defined the

practice of Sufism as the essence of Islam but also pointed to the

universality of its message. Other spiritualists, such as

G. I. Gurdjieff, may or may not conform to the tenets of Sufism as understood by orthodox Muslims.

Other noteworthy Sufi teachers who have been active in the West in recent years include

Bawa Muhaiyaddeen,

Inayat Khan,

Nazim Al-Haqqani,

Javad Nurbakhsh,

Bulent Rauf,

Irina Tweedie,

Idries Shah and

Muzaffer Ozak.

Currently active Sufi academics and publishers include

Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee,

Nuh Ha Mim Keller,

Abdullah Nooruddeen Durkee,

Waheed Ashraf and

Abdal Hakim Murad.

Theoretical perspectives in Sufism

The works of

Al-Ghazali firmly defended the concepts of Sufism within the

Islamic faith.

Traditional Islamic scholars have recognized two major branches

within the practice of Sufism, and use this as one key to

differentiating among the approaches of different masters and devotional

lineages.

[54]

On the one hand there is the order from the signs to the Signifier

(or from the arts to the Artisan). In this branch, the seeker begins by

purifying the lower self of every corrupting influence that stands in

the way of recognizing all of creation as the work of God, as God's

active Self-disclosure or theophany.

[55] This is the way of Imam

Al-Ghazali and of the majority of the Sufi orders.

On the other hand there is the order from the Signifier to His signs,

from the Artisan to His works. In this branch the seeker experiences

divine attraction (

jadhba),

and is able to enter the order with a glimpse of its endpoint, of

direct apprehension of the Divine Presence towards which all spiritual

striving is directed. This does not replace the striving to purify the

heart, as in the other branch; it simply stems from a different point of

entry into the path. This is the way primarily of the masters of the

Naqshbandi and

Shadhili orders.

[56]

Contemporary scholars may also recognize a third branch, attributed to the late

Ottoman scholar

Said Nursi and explicated in his vast Qur'an commentary called the

Risale-i Nur. This approach entails strict adherence to the way of Muhammad, in the understanding that this wont, or

sunnah, proposes a complete devotional spirituality adequate to those without access to a master of the Sufi way.

[57]

Contributions to other domains of scholarship

Sufism has contributed significantly to the elaboration of

theoretical perspectives in many domains of intellectual endeavor. For

instance, the doctrine of "subtle centers" or centers of subtle

cognition (known as

Lataif-e-sitta) addresses the matter of the awakening of spiritual intuition

[58] in ways that some consider similar to certain models of

chakra in Hinduism. In general, these subtle centers or

latâ'if

are thought of as faculties that are to be purified sequentially in

order to bring the seeker's wayfaring to completion. A concise and

useful summary of this system from a living exponent of this tradition

has been published by

Muhammad Emin Er.

[54]

Sufi psychology has influenced many areas of thinking both within and outside of Islam, drawing primarily upon three concepts.

Ja'far al-Sadiq (both an

imam in the

Shia

tradition and a respected scholar and link in chains of Sufi

transmission in all Islamic sects) held that human beings are dominated

by a lower self called the

nafs, a faculty of spiritual intuition called the

qalb or spiritual heart, and a spirit or soul called

ruh. These interact in various ways, producing the spiritual types of the tyrant (dominated by

nafs), the person of faith and moderation (dominated by the spiritual heart), and the person lost in love for God (dominated by the

ruh).

[59]

Of note with regard to the spread of Sufi psychology in the West is

Robert Frager, a Sufi teacher authorized in the

Khalwati Jerrahi

order. Frager was a trained psychologist, born in the United States,

who converted to Islam in the course of his practice of Sufism and wrote

extensively on Sufism and psychology.

[60]

Sufi cosmology and

Sufi metaphysics are also noteworthy areas of intellectual accomplishment.

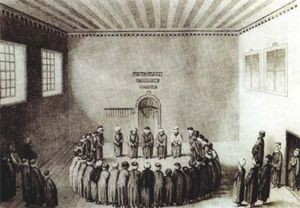

Sufi practices

Sufi gathering engaged in Dhikr

The devotional practices of Sufis vary widely. This is because an

acknowledged and authorized master of the Sufi path is in effect a

physician of the heart, able to diagnose the seeker's impediments to

knowledge and pure intention in serving God, and to prescribe to the

seeker a course of treatment appropriate to his or her maladies. The

consensus among Sufi scholars is that the seeker cannot self-diagnose,

and that it can be extremely harmful to undertake any of these practices

alone and without formal authorization.

[61]

Prerequisites to practice include rigorous adherence to Islamic norms

(ritual prayer in its five prescribed times each day, the fast of

Ramadan, and so forth). Additionally, the seeker ought to be firmly

grounded in supererogatory practices known from the life of Muhammad

(such as the "sunna prayers"). This is in accordance with the words,

attributed to God, of the following, a famous

Hadith Qudsi:

My servant draws near to Me through nothing I love more than that

which I have made obligatory for him. My servant never ceases drawing

near to Me through supererogatory works until I love him. Then, when I

love him, I am his hearing through which he hears, his sight through

which he sees, his hand through which he grasps, and his foot through

which he walks.

It is also necessary for the seeker to have a correct creed (

Aqidah),

[62] and to embrace with certainty its tenets.

[63]

The seeker must also, of necessity, turn away from sins, love of this

world, the love of company and renown, obedience to satanic impulse, and

the promptings of the lower self. (The way in which this purification

of the heart is achieved is outlined in certain books, but must be

prescribed in detail by a Sufi master.) The seeker must also be trained

to prevent the corruption of those good deeds which have accrued to his

or her credit by overcoming the traps of ostentation, pride, arrogance,

envy, and long hopes (meaning the hope for a long life allowing us to

mend our ways later, rather than immediately, here and now).

Sufi practices, while attractive to some, are not a

means for

gaining knowledge. The traditional scholars of Sufism hold it as

absolutely axiomatic that knowledge of God is not a psychological state

generated through breath control. Thus, practice of "techniques" is not

the cause, but instead the

occasion for such knowledge to be

obtained (if at all), given proper prerequisites and proper guidance by a

master of the way. Furthermore, the emphasis on practices may obscure a

far more important fact: The seeker is, in a sense, to become a broken

person, stripped of all habits through the practice of (in the words of

Imam

Al-Ghazali) solitude, silence, sleeplessness, and hunger.

[64]

Magic has also been a part of Sufi practice, notably in India.

[65]

This practice intensified during the declining years of Sufism in India

when the Sufi orders grew steadily in wealth and in political influence

while their spirituality gradually declined as they concentrated on

Saint worship, miracle working, magic and superstition. The external

religious practices were neglected, morals declined and learning was

despised. The element of magic in Sufism in India possibly drew from the

occult practices in the

Atharvaveda. The most famous of all Sufis,

Mansur Al-Hallaj (d. 922), visited Sindh in order to study "Indian Magic". He not only accepted Hindu ideas of

cosmogony and of divine descent but he also seems to have believed in the

Transmigration of the soul.

[66]

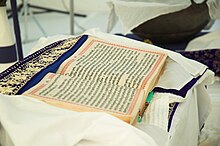

Dhikr

Allah as having been written on the disciple's heart according to Qadiri Al-Muntahi order

Dhikr is the remembrance of God commanded in the

Qur'an for all

Muslims through a specific devotional act, such as the repetition of divine names, supplications and aphorisms from

hadith literature and the Qur'an. More generally, dhikr takes a wide range and various layers of meaning.

[67]

This includes dhikr as any activity in which the Muslim maintains

awareness of God. To engage in dhikr is to practice consciousness of the

Divine Presence and

love,

or "to seek a state of godwariness". The Qur'an refers to Muhammad as

the very embodiment of dhikr of God (65:10-11). Some types of dhikr are

prescribed for all Muslims and do not require Sufi initiation or the

prescription of a Sufi master because they are deemed to be good for

every seeker under every circumstance.

[68]

Some Sufi orders

[69] engage in ritualized dhikr ceremonies, or

sema. Sema includes various forms of worship such as:

recitation,

singing (the most well known being the

Qawwali music of the Indian subcontinent),

instrumental music,

dance (most famously the

Sufi whirling of the

Mevlevi order),

incense,

meditation,

ecstasy, and

trance.

[70]

Some Sufi orders stress and place extensive reliance upon Dhikr. This practice of Dhikr is called

Dhikr-e-Qulb

(remembrance of Allah by Heartbeats). The basic idea in this practice

is to visualize the Arabic name of God, Allah, as having been written on

the disciple's heart.

[71]

Muraqaba

The practice of

muraqaba can be likened to the practices of

meditation attested in many faith communities. The word

muraqaba is derived from the same root (

r-q-b) occurring as one of the 99

Names of God in the Qur'an, al-Raqîb, meaning "the Vigilant" and attested in verse 4: 1 of the

Qur'an. Through

muraqaba,

a person watches over or takes care of the spiritual heart, acquires

knowledge about it, and becomes attuned to the Divine Presence, which is

ever vigilant.

While variation exists, one description of the practice within a Naqshbandi lineage reads as follows:

He is to collect all of his bodily senses in concentration, and to

cut himself off from all preoccupation and notions that inflict

themselves upon the heart. And thus he is to turn his full consciousness

towards God Most High while saying three times: "Ilahî anta maqsûdî wa-ridâka matlûbî—my

God, you are my Goal and Your good pleasure is what I seek". Then he

brings to his heart the Name of the Essence—Allâh—and as it courses

through his heart he remains attentive to its meaning, which is "Essence

without likeness". The seeker remains aware that He is Present,

Watchful, Encompassing of all, thereby exemplifying the meaning of his

saying (may God bless him and grant him peace): "Worship God as though

you see Him, for if you do not see Him, He sees you". And likewise the

prophetic tradition: "The most favored level of faith is to know that

God is witness over you, wherever you may be".[72]

Visitation

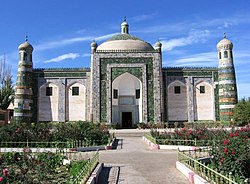

In popular Sufism (i.e., devotional practices that have achieved

currency in world cultures through Sufi influence), one common practice

is to visit or make pilgrimages to the tombs of saints, great scholars,

and righteous people. This is a particularly common practice in South

Asia, where famous tombs include those of Khoja Afāq, near

Kashgar, in China;

Lal Shahbaz Qalander, in

Sindh,Ali Hajwari in Lahore Bawaldin Zikrya in Multan Pakistan;

Moinuddin Chishti in

Ajmer, India;

Nizamuddin Auliya in

Delhi, India, and

Shah Jalal in

Sylhet, Bangladesh. Likewise, in

Fez, Morocco, a popular destination for such pious visitation is the

Zaouia Moulay Idriss II and the yearly visitation to see the current Sheikh of the Qadiri Boutchichi

Tariqah, Sheikh Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Boutchichi to celebrate the

Mawlid (which is usually televised on Moroccan National television).

Persecution

Sufis and Sufism has been subject to destruction of Sufi shrines and

mosques, suppression of orders and discrimination against adherents in a

number of Muslim countries where most Sufis live. The Turkish

Republican state banned all the different Sufi orders and closed their

institutions in 1925 after Sufis opposed the new secular order. The

Iranian Islamic Republic has harassed Shia Sufi, reportedly for their

lack of support for the government doctrine of "

velayat-e faqih" (i.e. that the supreme

Shiite

jurist should be the nation's political leader). In most other Muslim

countries, attacks on Sufis and especially their shrines has come from

some Muslims from the more puritanical schools of thought who believe

Sufi practices such as

celebration of the birthdays of Sufi saints, and

Dhikr ("remembrance" of God) ceremonies

[73] are

Bid‘ah or impure innovation, and polytheistic (

Shirk).

[74][75]

History

During the

Safavid era of

Iran,

"both the wandering dervishes of 'low' Sufism" and "the

philosopher-ulama of 'high' Sufism came under relentless pressure" from

power cleric

Muhammad Baqir Majlisi (d1110/1699). Majlisi—"one of the most powerful and influential"

Twelver Shi'a ulama

"of all time"—was famous (for among other things), suppression of

Sufism, which he and his followers believed paid insufficient attention

to Shariah law. Prior to Majlisi's rise, Shiism and Sufism had been

"closely linked".

[76]

In 1843 the

Senussi Sufi were forced to flee

Mecca and

Medina and head to

Sudan and

Libya.

[15][77]

Before the

First World War there were almost 100,000 disciples of the

Mevlevi order throughout the

Ottoman empire. But in 1925, as part of his desire to create a modern, western-orientated, secular state,

Atatürk banned all the different Sufi orders and closed their

tekkes.

Pious foundations were suspended and their endowments expropriated;

Sufi hospices were closed and their contents seized; all religious

titles were abolished and

dervish clothes outlawed. ... In 1937,

Atatürk went even further, prohibiting by law any form of traditional music, especially the playing of the ney, the Sufis' reed flute.

[78][79]

Current attacks

In recent years, Sufi shrines, and sometimes Sufi mosques, have been

damaged or destroyed in many parts of the Muslim world. Some Sufi

adherents have been killed as well.

Ali Gomaa, a Sufi scholar and Grand Mufti of

Al Azhar, has criticized the destruction of shrines and public property as unacceptable.

[80]

Pakistan

Since March 2005, 209 people have been killed and 560 injured in 29

different terrorist attacks targeting shrines devoted to Sufi saints in

Pakistan, according to data compiled by the Center for Islamic Research

Collaboration and Learning (CIRCLe).

[81]

At least as of 2010, the attacks have increased each year. The attacks

are generally attributed to banned militant organizations of

Deobandi or

Ahl-e-Hadith (Salafi) backgrounds.

[82] (Primarily Deobandi background according to another source—author John R. Schmidt).

[83] Deobandi and

Barelvi being the "two major sub-sects" of Sunni Muslims in South Asia

[84] that have clashed—sometimes violently—since the late 1970s in Pakistan.

[84] Although Barelvi are sometimes described as Sunni Sufis,

[85] whether the destruction and death is a result of Deobandi's persecution of Sufis is disputed.

[86])

In 2005, the militant organizations began attacking "symbols" of the

Barelvi community such as mosques, prominent religious leaders, and

shrines.

[82]

Timeline

- 2005

- 19 March: a suicide bomber kills at least 35 people and injured many

more at the shrine of Pir Rakhel Shah in remote village of Fatehpur

located in Jhal Magsi District of Balochistan. The dead included Shia and sunni devotees.[87]

- 27 May: As many as 20 people are killed and 100 injured when a

suicide-bomber attacks a gathering at Bari Imam Shrine during the annual

festival. The dead were mainly Shia.[88] According to the police members of Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) and Lashkar-i-Jhangvi (LJ) were involved.[89] Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), were arrested from Thanda Pani and police seized two hand grenades from their custody.[90][91]

- 2006

- 11 April: A suicide-bomber attacked a celebration of the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad (Eid Mawlid un Nabi) in Karachi's Nishtar Park organised by the Barelvi Jamaat Ahle Sunnat. 57 died including almost the entire leadership of the Sunni Tehrik; over 100 were injured.[92] Three people associated with Lashkar-i-Jhangvi were put on trial for the bombing.[93] (see: Nishtar Park bombing)

- 2007

- 18 December: The shrine of Abdul Shakoor Malang Baba is demolished by explosives.[94]

- 2008

- March 3: ten villagers killed in a rocket attack on the 400-year-old shrine of Abu Saeed Baba. Lashkar-e-Islam takes credit.[94]

- 2009

- 17 February: Agha Jee shot and killed in Peshwar, the fourth faith

healer killed over several months in Pakistan. Earlier Pir Samiullah was

killed in Swat by the Taliban 16 December 2008. His dead body was later

exhumed and desecrated. Pir Rafiullah was kidnapped from Nowshera and

his beheaded body was found in Matani area of Peshawar. Pir Juma Khan

was kidnapped from Dir Lower and his beheaded body was found near Swat.[95] Faith healing is associated with Sufi Islam in Pakistan

Pakistani faith healers are known as pirs, a term that applies to the

descendants of Sufi Muslim saints. Under Sufism, those descendants are

thought to serve as conduits to God. The popularity of pirs as a viable

healthcare alternative stems from the fact that, in much of rural

Pakistan, clinics don't exist or are dismissed as unreliable.[96]

- and suppressing it has been a cause of "extremist" Muslims there.[97]

- March 5: The shrine of Rahman Baba, "the most famous Sufi Pashto

language poet", razed to the ground by Taliban militants "partly because

local women had been visiting the shrine".[94][98]

- 8 March: Attack on shrine of "famous Sufi poet" Rahman Baba

in Peshawar. "The high intensity device almost destroyed the grave of

the Rehman Baba and the gates of a mosque, canteen and conference hall

situated in the spacious Rehman Baba Complex. Police said the bombers

had tied explosives around the pillars of the tombs, to pull down the

mausoleum".[99]

- May 8: shrine of Shaykh Omar Baba destroyed.[94][100]

- 12 June: Mufti Sarfraz Ahmed Naeemi killed by suicide bomber in

Lahore. A leading Sunni Islamic cleric in Pakistan he was well known for

his moderate views and for publicly denouncing the Taliban’s beheadings

and suicide bombings as "un-Islamic".[101]

- 2010

- 22 June: Taliban militants blow up the Mian Umar Baba shrine in Peshawar. No fatalities reported.[94][102]

- 1 July: Multiple bombings of Data Durbar Complex Sufi shrine, in

Lahore, Punjab. Two suicide bombers blew themselves up killing at least

50 people and injuring 200 others.[94]

- 7 October: 10 people killed, 50 injured in a double suicide bombing attack on Abdullah Shah Ghazi shrine in Karachi[103]

- 7 October: The tomb of Baba Fariddudin Ganj Shakkar in Pakpattan is attacked. Six people were killed and 15 others injured.[94]

- 25 October: 6 killed, and at least 12 wounded in an attack on the

shrine of 12th-century saint, Baba Farid Ganj Shakar in Pakpattan.[104]

- 14 December: Attack on Ghazi Baba shrine in Peshawar, 3 killed.[105]

- 2011

- 3 February: Remote-controlled device is triggered as food is being

distributed among the devotees outside the Baba Haider Saieen shrine in

Lahore, Punjab. At least three people were killed and 27 others injured.[94]

- 3 April: Twin suicide attack leaves 42 dead and almost a hundred

injured during the annual Urs festival at shrine of 13th century Sufi

saint Sakhi Sarwar (a.k.a. Ahmed Sultan) in the Dera Ghazi Khan district

of Punjab province. Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claims

responsibility for the attack.[94][106]

- 2012

- 21 June: Bomb kills three people and injures 31 others at the Pinza Piran shrine in Hazarkhwani in (Peshwar).

"A police official said the bomb was planted in a donkey-cart that went

off in the afternoon when a large number of people were visiting the

popular shrine".[107]

Kashmir

In this predominately Muslim, traditionally Sufi region,

[108]

some six places of worship have been either completely or partially

burnt in "mysterious fires" in several months leading up to November

2012.

[109] The most prominent victim of damage was the Dastageer Sahib Sufi shrine in

Srinagar which burned in June 2012, injuring 20.

[110]

While investigators have so far found no sign of arson, according to

journalist Amir Rana the fires have occurred within the context of a

surging Salafi movement which preaches that "Kashmiri tradition of

venerating the tombs and relics of saints is outside the pale of Islam".

[109]

mourners outside the burning shrine cursed the Salafis

for creating an atmosphere of hate, [while] some Salafis began posting

incendiary messages on Facebook, terming the destruction of the shrine a

"divine act of God".[109]

Somalia

Under the Al-Shabab rule in Somali, Sufi ceremonies were banned

[111] and shrines

destroyed.

[112] As the power of Al-Shabab has waned, however, Sufi ceremonies are said to have "re-emerged".

[108]

Mali

In the ancient city of Timbuktu, sometimes called "the city of 333 saints",

UNESCO

reports that as many as half of the city’s shrines "have been destroyed

in a display of fanaticism", as of July 2012. A spokesman for

Ansar Dine

has stated that "the destruction is a divine order", and that the group

had plans to destroy every single Sufi shrine in the city, "without

exception".

[113] In

Gao and

Kidal, as well as Timbuktu, Salafi Islamists have destroyed musical instruments and driven musicians (

music is not

Haraam under Sufi Islam) into "economic exile" away from Mali.

[114]

International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda described the Islamists’ actions as a "war crime".

[115][116]

Egypt

A May 2010 ban by the ministry of awqaf (religious endowments) of centuries old Sufi

dhikr

gatherings (devoted to the remembrance of God, and including dancing

and religious songs) has been described as a "another victory for

extreme Salafi thinking at the expense of Egypt's moderate Sufism".

Clashes followed at

Cairo's

Al-Hussein Mosque and al-Sayyida Zeinab mosques between members of Sufi orders and security forces who forced them to evacuate the two shrines.

[73]

In 2009 the moulid of al-Sayyida Zeinab, the prophet's Muhammad's

granddaughter, was banned ostensibly over concern over the spread of

swine flu

[117] but also at the urging of Salafis.

[73]

According to Gaber Qassem, deputy of the Sufi Orders, approximately

14 shrines have been violated in Egypt since the January 2011

revolution. According to Sheikh Tarek El-Rifai, head of the Rifai Sufi

Order, a number of Salafis have prevented Sufi prayers in Al-Haram.

Sheikh Rifai said that the order's lawyer has filed a report at the

Al-Haram police station to that effect. In early April 2011, a Sufi

march from Al-Azhar Mosque to Al-Hussein Mosque was followed by a

massive protest before Al-Hussein Mosque, "expressing outrage at the

destruction" of Sufi shrines. The Islamic Research Centre of Egypt, led

by Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmed El-Tayeb, has also renounced the attacks

on the shrines.

[75]

According to the Muslim Brotherhood website ikhwanweb.com, in 2011 "a

memorandum was submitted to the Armed Forces" citing 20 "encroachments"

on Sufi shrines.

[80]

Libya

Following the overthrow of

Muammar Gaddafi, several Sufi religious sites in Libya were deliberately destroyed or damaged.

[118]

In the weeks leading up to September 2012, "armed groups motivated by

their religious views" attacked Sufi religious sites across the country,

"destroying several mosques and tombs of Sufi religious leaders and

scholars".

[119]

Perpetrators were described as “groups that have a strict Islamic

ideology where they believe that graves and shrines must be desecrated.”

Libyan Interior Minister Fawzi Abdel A’al, was quoted as saying, “If

all shrines in Libya are destroyed so we can avoid the death of one

person [in clashes with security forces], then that is a price we are

ready to pay,”

[119]

In September 2012, three people were killed in clashes between

residents of Rajma (50 km south-east of Benghazi) and "Salafist

Islamists" trying to destroy a Sufi shrine in Rajma, the Sidi al-Lafi

mausoleum.

[120] In August 2012 the United Nations cultural agency

Unesco

urged Libyan authorities to protect Sufi mosques and shrines from

attacks by Islamic hardliners "who consider the traditional mystical

school of Islam heretical". The attacked have "wrecked mosques in at

least three cities and desecrated many graves of revered Sufi scholars".

[121]

Tunisia

In an article on the rise of Salafism in Tunisia, the media site

Al-Monitor reported that 39 Sufi shrines were destroyed or desecrated in Tunisia, from the 2011 revolution to January 2013.

[122]

Russia, Dagestan

Said Atsayev—also known as Sheikh Said Afandi al-Chirkavi—a prominent

74-year-old Sufi Muslim spiritual leader in Dagestan Russia, was killed

by a suicide bombing August 28, 2012 along with six of his followers.

His murder follows "similar religiously-motivated killings" in Dagestan

and other regions of ex-Soviet Central Asia, targeting religious

leaders—not necessarily Sufi—who are hostile to violent jihad. Afandi

had survived previous attempts on his life and was reportedly in the

process of negotiating a peace agreement between the Sufis and Salafis.

[123] [124][125]

Iran

According to

Seyed Mostafa Azmayesh,

an expert on Sufism and the representative of the Ni'matullāhī order

outside Iran, a campaign against the Sufis in Iran (or at least Shia

Sufis) began in 2005 when several books were published arguing that

because Sufis follow their own spiritual leaders do not believe in the

Islamic state's principle of "

velayat-e faqih" (i.e. that the supreme

Shiite

jurist should be the nation's political leader), Sufis should be

treated as second-class citizens. They should not be allowed to have

government jobs, and if they already have them, should be identified and

fired.

[126]

Since 2005 the

Ni'matullāhī

order—Iran's largest Sufi order—have come under increasing state

pressure. Three of their houses of worship have been demolished.

Officials accused the Sufis of not having building permits and of

narcotics possession—charges the Sufis reject.

[126]

The government of

Iran

is considering an outright ban on Sufism, according to the 2009 Annual

Report of the United States Commission on International Religious

Freedom.

[127] It also reports:

In February 2009, at least 40 Sufis in

Isfahan were arrested after protesting the destruction of a Sufi place of worship; all were released within days.

In January, Jamshid Lak, a Gonabadi Dervish from the Nematollahi Sufi

order was flogged 74 times after being convicted in 2006 of slander

following his public allegation of ill-treatment by a Ministry of

Intelligence official.

In late December 2008, after the closure of a Sufi place of worship,

authorities arrested without charge at least six members of the Gonabadi

Dervishes on

Kish Island and confiscated their books and computer equipment; their status is unknown.

In November 2008, Amir Ali Mohammad Labaf was sentenced to a

five-year prison term, 74 lashes, and internal exile to the southeastern

town of

Babak for spreading lies, based on his membership in the Nematollahi Gonabadi Sufi order.

In October, at least seven Sufi Muslims in Isfahan, and five others in

Karaj, were arrested because of their affiliation with the Nematollahi Gonabadi Sufi order; they remain in detention.

In November 2007, clashes in the western city of

Borujerd

between security forces and followers of a mystic Sufi order resulted

in dozens of injuries and the arrests of approximately 180 Sufi Muslims.

The clashes occurred after authorities began bulldozing a Sufi

monastery. It is unclear how many remain in detention or if any charges

have been brought against those arrested. During the past year, there

were numerous reports of Shi'a clerics and prayer leaders, particularly

in

Qom, denouncing Sufism and the activities of Sufi Muslims in the country in both sermons and public statements.

[127]

Not all Sufi's in Iran have been subject to government pressure.

Sunni dervish orders—such as the Qhaderi dervishes—in the

Sunni-populated parts of the country are thought by some to be seen as

allies of the government against Al-Qaeda.

[126]

Islam and Sufism

Sufism and Islamic law

Scholars and adherents of Sufism sometimes describe Sufism in terms of a threefold approach to God as explained by a tradition (

hadîth) attributed to Muhammad

[citation needed],

"The Canon is my word, the order is my deed, and the truth is my interior state".[citation needed] Sufis believe the

sharia (exoteric "canon"),

tariqa (esoteric "order") and

haqiqa ("truth") are mutually interdependent.

[128]

The

tariqa, the 'path' on which the mystics walk, has been defined as

[weasel words] 'the path which comes out of the

sharia, for the main road is called

branch, the path,

tariq.'

[clarification needed]

No mystical experience can be realized if the binding injunctions of

the sharia are not followed faithfully first. The tariqa however, is

narrower and more difficult to walk.

It leads the adept, called

salik or "wayfarer", in his

sulûk or "road" through different stations (

maqâmât) until he reaches his goal, the perfect

tawhîd, the existential confession that God is One.

[129]

Shaykh al-Akbar Muhiuddeen Ibn Arabi mentions, "When we see someone in

this Community who claims to be able to guide others to God, but is

remiss in but one rule of the Sacred Law – even if he manifests miracles

that stagger the mind – asserting that his shortcoming is a special

dispensation for him, we do not even turn to look at him, for such a

person is not a sheikh, nor is he speaking the truth, for no one is

entrusted with the secrets of God Most High save one in whom the

ordinances of the Sacred Law are preserved. (Jami' karamat al-awliya')".

[130]

The

Amman Message, a detailed statement issued by 200 leading Islamic scholars in 2005 in

Amman, and adopted by the Islamic world's political and temporal leaderships at the

Organisation of the Islamic Conference

summit at Mecca in December 2005, and by six other international

Islamic scholarly assemblies including the International Islamic Fiqh

Academy of Jeddah, in July 2006, specifically recognized the validity of

Sufism as a part of Islam—however the definition of Sufism can vary

drastically between different traditions (what may be intended is simple

tazkiah as opposed to the various manifestations of Sufism around the Islamic world).

[131]

Traditional Islamic thought and Sufism

The literature of Sufism emphasizes highly subjective matters that

resist outside observation, such as the subtle states of the heart.

Often these resist direct reference or description, with the consequence

that the authors of various Sufi treatises took recourse to allegorical

language. For instance, much Sufi poetry refers to intoxication, which

Islam expressly forbids. This usage of indirect language and the

existence of interpretations by people who had no training in Islam or

Sufism led to doubts being cast over the validity of Sufism as a part of

Islam. Also, some groups emerged that considered themselves above the

Sharia

and discussed Sufism as a method of bypassing the rules of Islam in

order to attain salvation directly. This was disapproved of by

traditional scholars.

For these and other reasons, the relationship between traditional

Islamic scholars and Sufism is complex and a range of scholarly opinion

on Sufism in Islam has been the norm. Some scholars, such as

Al-Ghazali, helped its propagation while other scholars opposed it.

W. Chittick explains the position of Sufism and Sufis this way:

In short, Muslim scholars who focused their

energies on understanding the normative guidelines for the body came to

be known as jurists, and those who held that the most important task was

to train the mind in achieving correct understanding came to be divided

into three main schools of thought: theology, philosophy, and Sufism.

This leaves us with the third domain of human existence, the spirit.

Most Muslims who devoted their major efforts to developing the spiritual

dimensions of the human person came to be known as Sufis.

Traditional and Neo-Sufi groups

The traditional Sufi orders, which are in majority, emphasize the

role of Sufism as a spiritual discipline within Islam. Therefore, the

Sharia (traditional Islamic law) and the

Sunnah

are seen as crucial for any Sufi aspirant. One proof traditional orders

assert is that almost all the famous Sufi masters of the past

Caliphates were experts in

Sharia and were renowned as people with great Iman (faith) and excellent practice. Many were also

Qadis

(Sharia law judges) in courts. They held that Sufism was never distinct

from Islam and to fully comprehend and practice Sufism one must be an

observant Muslim.

"Neo-Sufism" and "universal Sufism" are terms used to denote forms of

Sufism that do not require adherence to Shariah, or a Muslim faith. The

terms are not always accepted by those it is applied to. The

Universal Sufism movement was founded by

Inayat Khan, teaches the essential unity of all faiths, and accepts members of all creeds.

Sufism Reoriented is an offshoot of Khan's Western Sufism influenced by the

syncretistic teacher

Meher Baba. The

Golden Sufi Center exists in

England,

Switzerland and the

United States. It was founded by

Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee to continue the work of his teacher

Irina Tweedie, herself a disciple of the

Hindu Naqshbandi Sufi

Bhai Sahib. The Afghan-Scottish teacher

Idries Shah has been described as a neo-Sufi by the

Gurdjieffian James Moore.

[132] Other Western Sufi organisations include the Sufi Foundation of America and the

International Association of Sufism.

Western Sufi practice may differ from traditional forms, for instance

having mixed-gender meetings and less emphasis on the Qur'an.

Prominent Sufis

Geometric arabesque tiling on the underside of the dome of

Hafiz's tomb in

Shiraz.

Abul Hasan al-Shadhili

Abul Hasan al-Shadhili (died 1258 CE), the founder of the

Shadhiliyya Sufi order, introduced

dhikr jahri (The method of remembering Allah through loud means). Sufi orders generally preach to deny oneself and to destroy the ego-self

(nafs)

and its worldly desires. This is sometimes characterized as the "Order

of Patience-Tariqus Sabr". In contrast, Imam Shadhili taught that his

followers need not abstain from what Islam has not forbidden, but to be

grateful for what God has bestowed upon them.

[133]

This notion, known as the "Order of Gratitude-Tariqush Shukr", was

espoused by Imam Shadhili. Imam Shadhili gave eighteen valuable

hizbs (litanies) to his followers out of which the notable

Hizbul Bahr is recited worldwide even today.

Bayazid Bastami

Bayazid Bastami

(died 874 CE) is considered to be "of the six bright stars in the

firmament of the Prophet", and a link in the Golden Chain of the

Naqshbandi

Tariqah. He is regarded as the first mystic to openly speak of the

annihilation (fanā') of the base self in the Divine, whereby the mystic

becomes fully absorbed to the point of becoming unaware of himself or

the objects around him. Every existing thing seems to vanish, and he

feels free of every barrier that could stand in the way of his viewing

the Remembered One. In one of these states, Bastami cried out: "Praise

to Me, for My greatest Glory!" His belief in the unity of all religions

became apparent when asked the question: "How does Islam view other

religions?" His reply was "All are vehicles and a path to God's Divine

Presence".

Ibn Arabi

Muhyiddin Muhammad b. 'Ali

Ibn 'Arabi

(or Ibn al-'Arabi) AH 561- AH 638 (July 28, 1165 – November 10, 1240)

is considered to be one of the most important Sufi masters, although he

never founded any order (

tariqa). His writings, especially

al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya and Fusus al-hikam, have been studied within all

the Sufi orders as the clearest expression of

tawhid (Divine Unity), though because of their

recondite nature they were often only given to initiates. Later those who followed his teaching became known as the school of

wahdat al-wujud

(the Oneness of Being). He himself considered his writings to have been

divinely inspired. As he expressed the Way to one of his close

disciples, his legacy is that 'you should never ever abandon your

servanthood ('

ubudiyya), and that there may never be in your soul a longing for any existing thing'.

[134]

Junayd Baghdadi

Junayd Baghdadi

(830-910 CE) was one of the great early Sufis, and is a central figure

in the golden chain of many Sufi orders. He laid the groundwork for

sober mysticism in contrast to that of God-intoxicated Sufis like

al-Hallaj, Bayazid Bastami and Abusaeid Abolkheir. During the trial of

al-Hallaj, his former disciple, the Caliph of the time demanded his

fatwa. In response, he issued this fatwa: "From the outward appearance

he is to die and we judge according to the outward appearance and God

knows better". He is referred to by Sufis as Sayyid-ut Taifa, i.e. the

leader of the group. He lived and died in the city of Baghdad.

Mansur al-Hallaj

Mansur al-Hallaj

(died 922 CE) is renowned for his claim "Ana-l-Haqq" (I am The Truth).

His refusal to recant this utterance, which was regarded as

apostasy,

led to a long trial. He was imprisoned for 11 years in a Baghdad

prison, before being tortured and publicly dismembered on March 26, 922.

He is still revered by Sufis for his willingness to embrace torture and

death rather than recant. It is said that during his prayers, he would

say "O Lord! You are the guide of those who are passing through the

Valley of Bewilderment. If I am a heretic, enlarge my heresy".

[135]

Reception

Sufism did not always enjoy wide acceptance. Especially in its early stages, Muslim

Ulema looked down on Sufi practices as a form of extremism in religion.

[136]

Perception outside Islam

A choreographed Sufi performance on Friday at Sudan.

Sufi mysticism has long exercised a fascination upon the Western world, and especially its orientalist scholars.

[137] Figures like

Rumi have become well known in the United States, where Sufism is perceived as a peaceful and apolitical form of Islam.

[137]

The

Islamic Institute in Mannheim, Germany, which works towards the integration of

Europe

and Muslims, sees Sufism as particularly suited for interreligious

dialogue and intercultural harmonisation in democratic and pluralist

societies; it has described Sufism as a symbol of tolerance and

humanism—nondogmatic, flexible and non-violent.

[138]

Influence of Sufism on Judaism

Although the monotheism of Sufism (and of Islam altogether) is a

variation of the Jewish tradition, and the whole concept of shari'ah is

simply an islamization of the Jewish notion of halacha (which preceded

it by 1,000 years), there is also evidence that the influence moved in

the opposite direction as well—that Sufism did also influence the

development of some schools of Jewish philosophy and ethics. A great

influence was exercised by Sufism upon the ethical writings of Jews in

the

Middle Ages[citation needed]. In the first writing of this kind, we see "Kitab al-Hidayah ila Fara'iḍ al-Ḳulub",

Duties of the Heart, of

Bahya ibn Paquda. This book was translated by

Judah ibn Tibbon into

Hebrew under the title "Ḥovot ha-Levavot".

[139]

The precepts prescribed by the

Torah number 613 only; those dictated by the intellect are innumerable.

This was precisely the argument used by the Sufis against their adversaries, the

Ulamas.

The arrangement of the book seems to have been inspired by Sufism. Its

ten sections correspond to the ten stages through which the Sufi had to

pass in order to attain that true and passionate love of God which is

the aim and goal of all ethical self-discipline. A considerable amount

of Sufi ideas entered the Jewish mainstream

[citation needed] through Bahya ibn Paquda's work, which remains one of the most popular ethical treatises in Judaism

[citation needed].

It is noteworthy that in the ethical writings of the Sufis

Al-Kusajri and

Al-Harawi[disambiguation needed]

there are sections which treat of the same subjects as those treated in

the "Ḥovot ha-Lebabot" and which bear the same titles: e.g., "Bab

al-Tawakkul"; "Bab al-Taubah"; "Bab al-Muḥasabah"; "Bab al-Tawaḍu'";

"Bab al-Zuhd". In the ninth gate, Baḥya directly quotes sayings of the

Sufis, whom he calls

Perushim. However, the author of the

Ḥovot ha-Levavot

did not go so far as to approve of the asceticism of the Sufis,

although he showed a marked predilection for their ethical principles.

The Jewish writer Abraham bar Ḥiyya teaches the asceticism of the

Sufis. His distinction with regard to the observance of Jewish law by

various classes of men is essentially a Sufic theory. According to it

there are four principal degrees of human perfection or sanctity;

namely:

- 1. of "Shari'ah", i.e., of strict obedience to all ritual laws of Islam,

such as prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, almsgiving, ablution, etc., which

is the lowest degree of worship, and is attainable by all

- 2. of Ṭariqah, which is accessible only to a higher class of

men who, while strictly adhering to the outward or ceremonial

injunctions of religion, rise to an inward perception of mental power

and virtue necessary for the nearer approach to the Divinity

- 3. of "Ḥaḳikah", the degree attained by those who, through

continuous contemplation and inward devotion, have risen to the true

perception of the nature of the visible and invisible; who, in fact,

have recognized the Godhead, and through this knowledge have succeeded

in establishing an ecstatic relation to it; and

- 4. of the "Ma'arifah", in which state man communicates directly with the Deity.

Abraham ben Moses ben Maimon, the son of the Jewish philosopher

Maimonides,

believed that Sufi practices and doctrines continue the tradition of

the Biblical prophets. See Sefer HaMaspik, "HaPrishut", Chapter 11

("Ha-ma’avak") s.v. hitbonen eifo bi-masoret mufla’ah zu, citing the

Talmudic explanation of Jeremiah 13:27 in Chagigah 5b; in Rabbi Yaakov

Wincelberg’s translation, "The Way of Serving God" (Feldheim), p. 429

and above, p. 427. Also see ibid., Chapter 10 ("Ikkuvim"), s.v. va-halo

yode’a atah; in "The Way of Serving God", p. 371. There are other such

references in Rabbi Abraham’s writings, as well.> He introduced into

the Jewish prayer such practices as reciting God's names (

dhikr)

[citation needed].

Abraham Maimuni's principal work is originally composed in

Judeo-Arabic and entitled "כתאב כפיא אלעאבדין"

Kitāb Kifāyah al-'Ābidīn

("A Comprehensive Guide for the Servants of God"). From the extant

surviving portion it is conjectured that Maimuni's treatise was three

times as long as his father's Guide for the Perplexed. In the book,

Maimuni evidences a great appreciation for, and affinity to, Sufism.

Followers of his path continued to foster a Jewish-Sufi form of pietism

for at least a century, and he is rightly considered the founder of this

pietistic school, which was centered in

Egypt.

The followers of this path, which they called, interchangeably,

Hasidism (not to confuse with the latter Jewish Hasidic movement) or

Sufism (Tasawwuf), practiced spiritual retreats, solitude, fasting and

sleep deprivation. The Jewish Sufis maintained their own

brotherhood, guided by a religious leader—like a Sufi

sheikh.

[140]

Abraham Maimuni's two sons, Obadyah and David, continued to lead this Jewish-Sufi brotherhood. Obadyah Maimonides wrote

Al-Mawala Al Hawdiyya

("The Treatise of the Pool")—an ethico-mystical manual based on the

typically Sufi comparison of the heart to a pool that must be cleansed

before it can experience the Divine.

The Maimonidean legacy extended right through to the 15th century

with the 5th generation of Maimonidean Sufis, David ben Joshua

Maimonides, who wrote

Al-Murshid ila al-Tafarrud (The Guide to Detachment), which includes numerous extracts of

Suhrawardi[disambiguation needed]'s

Kalimat at-Tasawwuf.

[citation needed]

Popular culture

Films

In

The Jewel of the Nile (1985), the eponymous Jewel is a Sufi holy man.

In

Hideous Kinky (1998), Julia (

Kate Winslet) travels to

Morocco to explore Sufism and a journey to self-discovery.

In

Monsieur Ibrahim (2003),

Omar Sharif's character professes to be a Muslim in the Sufi tradition.

Bab'Aziz (2005), a film by

Tunisian director

Nacer Khemir, draws heavily on the Sufi tradition, containing quotes from Sufi poets such as

Rumi and depicting an ecstatic Sufi dance.

Music

Friday evening ceremony at Dargah Salim Chisti, India.

Abida Parveen, a Pakistani Sufi singer is one of the foremost exponents of Sufi music, together with

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan are considered the finest Sufi vocalists of the modern era.

Sanam Marvi another Pakistani singer has recently gained recognition for her Sufi vocal performances.

A. R. Rahman, the Oscar-winning Indian musician, has several compositions which draw inspiration from the Sufi genre; examples are the

filmi qawwalis Khwaja Mere Khwaja in the film

Jodhaa Akbar,

Arziyan in the film

Delhi 6 and

Kun Faya Kun in the film

Rockstar.

Bengali singer

Lalan Fakir and Bangladesh's national poet

Kazi Nazrul Islam scored several Sufi songs.

Junoon, a band from

Pakistan, created the genre of

Sufi rock by combining elements of modern

hard rock and traditional folk music with Sufi poetry.

In 2005,

Rabbi Shergill released a Sufi rock song called "

Bulla Ki Jaana", which became a chart-topper in India and Pakistan.

[141][142]

Madonna, on her 1994 record

Bedtime Stories, sings a song called "

Bedtime Story"

that discusses achieving a high unconsciousness level. The video for

the song shows an ecstatic Sufi ritual with many dervishes dancing,

Arabic calligraphy and some other Sufi elements. In her 1998 song

"Bittersweet", she recites Rumi's poem by the same name. In her 2001

Drowned World Tour, Madonna sang the song "Secret" showing rituals from

many religions, including a Sufi dance.

Singer/songwriter

Loreena McKennitt's record

The Mask and Mirror (1994) has a song called "The Mystic's Dream" that is influenced by Sufi music and poetry. The band

mewithoutYou has made references to Sufi parables, including the name of their album

It's All Crazy! It's All False! It's All a Dream! It's Alright (2009).

Tori Amos makes a reference to Sufis in her song "Cruel".

Mercan Dede is a Turkish composer who incorporates Sufism into his music and performances.

Literature

The Persian poet

Rumi

has become one of the most widely read poets in the United States,

thanks largely to the interpretative translations published by

Coleman Barks.

[143] Elif Safak's novel

The Forty Rules of Love tells the story of Rumi becoming a disciple of the Sufi dervish

Shams Tabrizi.

Modern/contemporary Sufi scholars

Arabian Peninsula

Levant and Africa

Western Europe

Eastern Europe

North America

South Asia

Eastern and Central Asia

Photo gallery